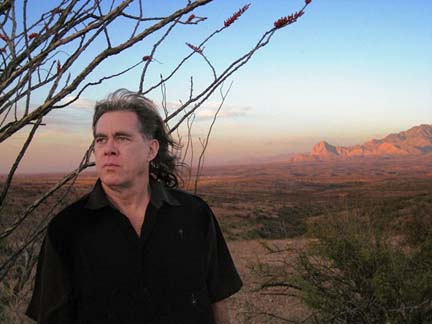

Musician Steve Roach is interviewed by Mathias Wagner of KULTUR!NEWS.

Excerpted below:

Steve Roach: You could say “verse-chorus-verse” is a classic form for translating into sound the way the human mind in our culture perceives things. The “slow river” that you speak of is my way of striving to translate the way the mind of nature works. That’s what my wife says anyway, and in thinking about it, I have to agree. As a writer and music critic, she spends a lot of time researching such things. In fact, she says that living with me and watching me work has given her the opportunity to analyze in depth my particular artistic process as it unfolds and compare it with others. So generally, I make music, and she takes the time to figure out how and why I did it, which makes for a lot of interesting discussions in our house. Her take on this whole question involves “the human ability to experience much more sensory input and emotional nuance than our conscious minds can pinpoint, remember and describe.”

For instance, if I compose a piece of music after watching an incredible sunset in the desert, I want to capture and communicate as much of that experience as possible: The indescribable colors that transmute through the sky in all directions as the earth slowly turns. The sounds of the wind blowing through the cactuses. The coyotes howling. The birds chirping and whizzing by. The quality of warmth in the air. And, perhaps most important, all the feelings that pass over and through me while this is happening. These things cannot be put into words. A painter might be able to capture the scenery and color of any given moment, but on a piece of canvas, you can’t express the slow transformation of the entire landscape and the continually evolving effect it’s having on you.

A verse-chorus-verse formula is too rigid for this kind of expression as well. In such music, you can successfully convey the more conscious feelings you had, and surround them with a certain amount of musical nuance to fill out the picture. But when you were watching that sunset, all kinds of feelings, thoughts, senses and perceptions flowed vividly through each other and were inseparable. The immense number of details cannot be singled out and consciously acknowledged. Yet as you sit out there and take in this sunset, the flow of it all does “change your mind and feelings,” as you said earlier.

As a way of trying to describe the significance of what I’m doing, we came up with a quote by Paul LaViolette, who is head of an interdisciplinary research foundation in Oregon. He says that whenever we form a thought, we in effect simplify the nuance-filled complexity of the world. We also simplify our own feelings in reponse to that world. He says that it’s beneficial to be able “to tune into feelings before they get abstracted into a thought. People who can do this are able to directly tune into data of far greater complexity. Such sensitivity fosters creativity and the ability to see things in new ways.”

For me to try to squeeze the experiences that inspire my music into a verse-chorus form (just because that’s the way some people think music should be written) is to ignore the incredible wealth of nuance that can be expressed in music. I let the tempo and rhythm of the experiences that inspire me shape the music. In terms of nature and my response to it, that form happens to remind you of a slow river flowing silently. The real key is what you said right after that: “one doesn’t miss any detail when not looking at it, but after a while the flowing begins to change one’s mind and feelings.” I think your description is about as close as it comes to conveying something that, in reality, can never be described in words.